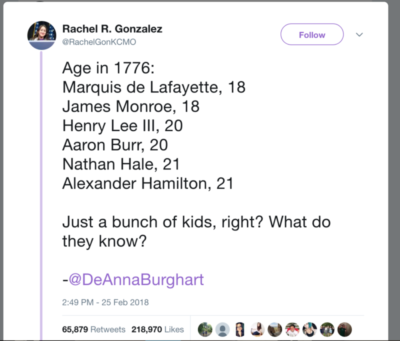

A meme making its way around the Internet speaks volumes to the marvel that young students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School — not yet eligible to vote — are leading a revolution in the politics of guns.

Note this list contains no women — not even Betsy Ross, who at 24, as a trained upholsterer, made tents and blankets for the Continental Army. She also hand-sewed the first American flag, convincing George Washington to change his design of the stars from six points to five — far easier and thus faster to sew, she assured him.

As we celebrate Women’s History Month, it is important to remember that young women were often at the forefront of social change. And as the author of Gilded Suffragists, a new book on the Votes for Women campaign, I wanted to share the story of Alice Paul, who at the age of 28 lead a parade in Washington, D.C. that shook up the president, Congress, the local police, the political establishment — and older suffrage advocates.

As you can see from the flyer, Alice Paul — who had learned suffrage tactics while a member of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union in England — left no detail to chance. She found talented artists to convey a procession of proud, strong, beautiful suffragists. She staged pageants, with German actress Hedwig Reicher posing as “Columbia” in front of the Treasury Department. And she reached out to the young — “youthful activity rang from every corner” of headquarters, said one activist. By one count, the procession featured 8,000 marchers, 9 bands, 4 mounted brigades, 20 floats and that theatrical tableau on the steps of government’s bank.

Police officials at first suggested she stage her march along Sixteenth Street, with its respectable middle class homes. But Paul understood symbolism, and worked connections to win approval for Pennsylvania Avenue – where Woodrow Wilson‘s first inaugural parade would take place the following day. The Inaugural Committee had banned women from marching on March 4, so Paul gave women a day to showcase their own citizenship.

It was a procession meant to announce the arrival of a new generation of activists, eager to rebrand a tired movement. Paul had arranged floats depicting the six states that had already granted full suffrage to women, and the states now seeking it. The Liberty Bell in Philadelphia was represented on one float, followed by signage outlining the first 75 years of the woman’s rights struggle on the next. As for the marchers, they walked in professional affiliation, each group wearing a different color – actresses in rose, librarians in blue – giving the affair a rainbow cast. At the parade’s head, in a flowing white cape atop a white horse named Gray Dawn rode Inez Milholland, a brilliant orator and fierce beauty, the movement’s Joan of Arc. In her wake came the parade’s message: “We demand an amendment to the United States Constitution enfranchising women of the country.”

Despite the vast planning and expenditure of talent, time and money, in the end the parade was marred by the haunting shadow of racial discrimination, and the stubborn menace of gender anger. Southern suffragists had threatened to boycott the march when word spread that students from Howard University’s Delta Sigma Theta Sorority planned to join. Paul mingled them with other college students. Ida B. Wells, a journalist who had awakened the nation to the injustice of lynching young black men, was president of a Chicago-based black suffrage group, the Alpha Club. She too wanted to march with the rest of the suffragists, in the Illinois delegation. Alice Paul demurred, fearing southern defections. A defiant Wells waited on the sidewalk until the Illinois delegation came in view, and then squeezed in between two friends who assisted in the feint.

Some 25,000 spectators waited. With no police restraint, male hoodlums hostile to the cause waded into the parade route and spit on or abused the marchers. By day’s end, 100 marchers were hospitalized, and the political establishment was roused to action. Local police, either overwhelmed or indifferent, did nothing to open the route. One of Paul’s top lieutenants, Elizabeth Seldon Rogers, called her brother-in-law, Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Literally, he sent in the cavalry, and they cleared the streets one block at a time.

The next morning’s newspapers told a story of dueling impressions. “Woman’s Beauty, Grace and Art Bewilder the Capital,” headlined the Washington Post in one front-page account.” Another front-page story, this one in the Chicago Daily Tribune, noticed “Mobs at Capital Defy Police; Block Suffrage Parade.” As the New York Tribune observed a few days later, “Capital Mobs Made Converts to Suffrage.”

A congressional committee investigated. The D.C. superintendent of police was fired. At the next meeting of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association, Alice Paul received a rousing reception. Behind the scenes, the group’s leaders were sharpening their knives. They had authorized the parade by their young protege, but they felt upstaged. So they booted her, claiming she had misused funds, something Alice Paul denied.

A few years later, Alice Paul met NAWSA leader Carrie Chapman Catt for the last time.

Between them was a gap of twenty-six years, a generational divide that greatly influenced their tactics. Catt was schooled in a history of disappointment, wary of the fickleness of political promise and public support. Paul was fueled by the confidence of youth, sure of victory.

As she began her American suffrage activism in 1913, the 28-year-old Paul thought a federal amendment was within her grasp. The 54-year-old Catt worried that she would not live to see a constitutional guarantee. In an oral history interview years later, Paul recalled, “I remember one time that I did actually talk to her. I remember she said, ‘I have always felt that I enlisted for life when I went into this movement.’ She was opposing the idea that we had that we might be able to get the vote. She said, ‘When you have more experience you’ll know that it’s a much longer fight than you have any idea of.’ ”

Seems this is often the way, the wise older heads giving way to the more confident young ones.